Bohemia was ‘Vampire Central’

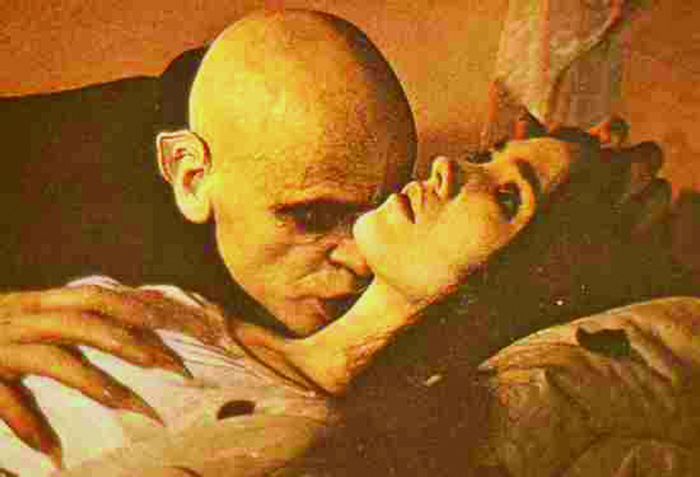

One of the most common themes in Bohemian folklore is that of the vampire. Dating back to the 11th Century, people believed in the existence of such creatures and in Bohemia, in Czechoslovakia and much of Eastern Europe, these stories and beliefs were rife right up until the end of the 19th Century. Although in today’s society vampires are primarily considered to be creatures of myth and legend and are generally disregarded as such, throughout history they have been both believed and feared, and there have been many accounts and testimonies insisting on their existence.

In the year 1047, the words ‘Upir Lichy’ were first written in a document describing a Russian prince and directly translated, the words mean ‘Wicked Vampire’ in Russian, Czech and Slovakian. This is possibly the earliest reference to the existence and belief of vampires, although the word did not enter the English vocabulary until 1734, where it was eventually translated from the German after accounts of the European waves of vampire hysteria. Although in 1190, Latin author Walter Map included accounts of vampire-like creatures in England in his major surviving work, De Nugis Curialium.

One of the earliest recorded tales of vampirism however dates back to around 1250 in Liebava, a town not far from Olmutz in Czechoslovakia and home to the original Bohemians. The legend tells of a vampire who would leave his tomb in the local cemetery at night and walk into the town as a supposed creature of the night and attack sleeping women and children, before returning to his crypt before sunrise. People who had witnessed the creature had identified him as a leading citizen of the community who had recently died. The legend has it that a vampire hunter was summoned from neighbouring Hungary to rid the town of the vampire and after hearing the story, the hunter proceeded to watch the tomb for several nights from the safety of the church’s bell tower. On the night the creature was defeated, the hunter watched him walk into town and then snuck down from the tower to steal the vampire’s shroud before returning to his place of safety. The story goes that on the creature’s return he was so maddened to find his possessions taken that he let out a deathly howl and began to climb the bell tower where the hunter had been hiding, to reclaim what was his. As he did so, he was attacked by the vampire hunter, who was armed with only a shovel, and later beheaded to ensure that he could not rise once more.

In 1337, the hysteria hit Bohemia and several different reports indicated the manifestation of vampires in the cloisters of a church at Opatowicze. It wasn’t until the area was exorcised and protected with holy water and crucifixes, that the reports ended.

Montague Summers, author of The Vampire in Europe, which was published in 1929, said that the province of Bohemia was stronger in vampire beliefs than anywhere else and was the centre of vampire activity. It is thought that this was the case and that the whole of Czechoslovakia was infested up until the industrial revolution at the turn of the 16th century. Historical and recent findings seem to corroborate this belief.

According to Summers, in the village of Blov in western Bohemia, a herdsman had risen after his death and begun attacking and murdering fellow villagers as a creature of the night. To stop his bloody killing spree, the community exhumed his body from his grave and drove a large stake through his heart, making sure he was pinned to the ground. The story goes that later that same night the dead herdsman rose again and continued his murderous escapades, even gloating that they had “given [him] a fine stick to drive the dogs away.” The killing was only finally stopped when his body was cremated.

Throughout the modern ages, archaeologists have uncovered many vampire graves, revealing the bones of dismembered and staked skeletons, both popular methods of eradicating vampires, which have since been transferred to the silver screen time and time again. Often, the vampires’ bodies would be found either face down or buried lying north to south – treatment that was reserved only for that of the damned. In 1966 in Celakovice, near Prague, 14 vampire graves were uncovered with the skeletons dating back to the 10th century. The bodies had been beheaded and stones were found in their mouths and although it was rumoured at the time that they also had fangs, the archaeologists denied this claim.

An article published in the Prague Post by Katka Fronk, entitled ‘Bohemian Vampires Rise Again’, describes Bohemia as ‘Vampire Central.’ It seems the existence of vampires, although commonly disregarded as myth, will never be either conclusively proved or disproved. With uncountable witness statements and various reports of vampirism traceable throughout history, perhaps the question should not be ‘did vampires exist?’ but rather ‘where are they now?’

Leave a Response

You must be logged in to post a comment.