Bohemia loses a true son of the soil

Peter Powell’s friend, Susan King, writes:

Bohemia lost one of its great characters when Peter Powell died at the end of July. Many local residents knew Peter, by sight if not by name. He always wore country clothing, either farmworker’s attire of corduroy trousers, moleskin waistcoat, red neckerchief and cap, or impeccable in tweeds, handkerchief just so in his breast pocket, watch and chain in his waistcoat.

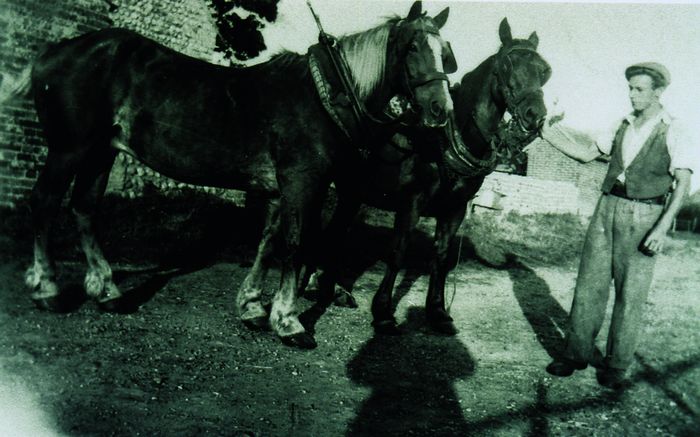

Peter died of viral pneumonia at the Conquest, aged eighty-nine. He worked on farms all his life, and for thirty years was a horseman on the land. He turned his hand to everything. He looked after a herd of two hundred Jersey cows, sheep, pigs, chickens, ducks, hedged and ditched, thatched, built a wide variety of farm buildings, and was a craftsman in everything he did. During half a century of farming he built up a reputation as the best farmworker in East Sussex.

Born in Horntye Road in 1920, whenever Peter went missing as a child he was always found with the animals at the local area known as Hickman’s Fields. Leaving Mags School at fourteen, he went to work for Jack Verity at Barnhorn, west of Bexhill.

He said, “Old Man Verity was as tough as old boots, but I loved him like a father. He taught me farming. When I left he said I was the best farmworker he had ever had.” Peter had a fund of farming stories, some tragic, some amusing, and all were gripping, as he was a brilliant raconteur. At first Peter lived in a ground floor room at the farmhouse with another young lad. “We had to get up at four o’clock in the morning to feed the horses, and Verity would dance in his hob-nailed boots on the floor of the room above to wake us up. Sometimes we would creep out of the window up to the byre and then start singing at the tops of our voices, just to let him know he was dancing above an empty room!”

When Peter brought his horses home in the evening, he would often meet an old man of about ninety, bringing home a team of oxen to the neighbouring farm. “He would laugh at me and my horses, saying farming with horses was a new-fangled idea and they would never replace oxen.”

When World War Two broke out, Peter wanted to join up, but was told he had to stay on the farm as it was a reserved occupation. However, Barnhorn was in a very dangerous position. Anti-aircraft guns were mounted on the hills behind, and the farm was often caught in cross-fire between them and incoming German planes. The British government posed a danger too: the coast was mined in case of invasion. One day Peter was ploughing a field and a man he knew greeted him en route to the golf course. A little later, Peter saw him climb over the fence back into the field after a golf ball. He stood on a land mine and was blown up. If that hadn’t happened, Peter and his horses would have gone over the land mine later. No-one had told the farmer they’d mined his field.

Peter and his horses ploughed, sowed and reaped the fields that lie dreaming under Ravenside Shopping Centre, before the gasworks were there, and the fields underlying the former Northeye Prison. “Just a few days before harvest the government requisitioned it. They wouldn’t let me harvest the crop. They just destroyed it all.”

Peter met his wife, Dorothy, when she came to work on the farm as a Land Girl. The couple had five children, Anne, William, John, Jane and Andrew, who died as a baby. Peter briefly worked for Lord Astor at Cliveden. His job included loading the guns for shooting parties. Animal-loving Peter returned to Barnhorn. With a growing family, Peter eventually left Barnhorn and worked for Lady Killearn at Haremere Hall, Etchingham. Lady Killearn was a tartar. Peter said, “I thought I was bettering myself, but it was the worst mistake I ever made in my life.” On one occasion he confronted, single-handed, a thief cracking Lady Killearn’s safe at midnight. He also survived being run over by a tractor.

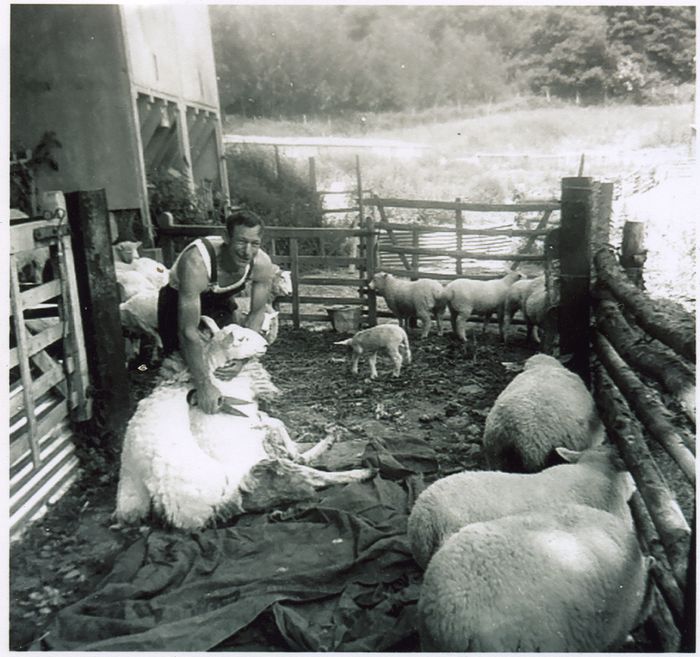

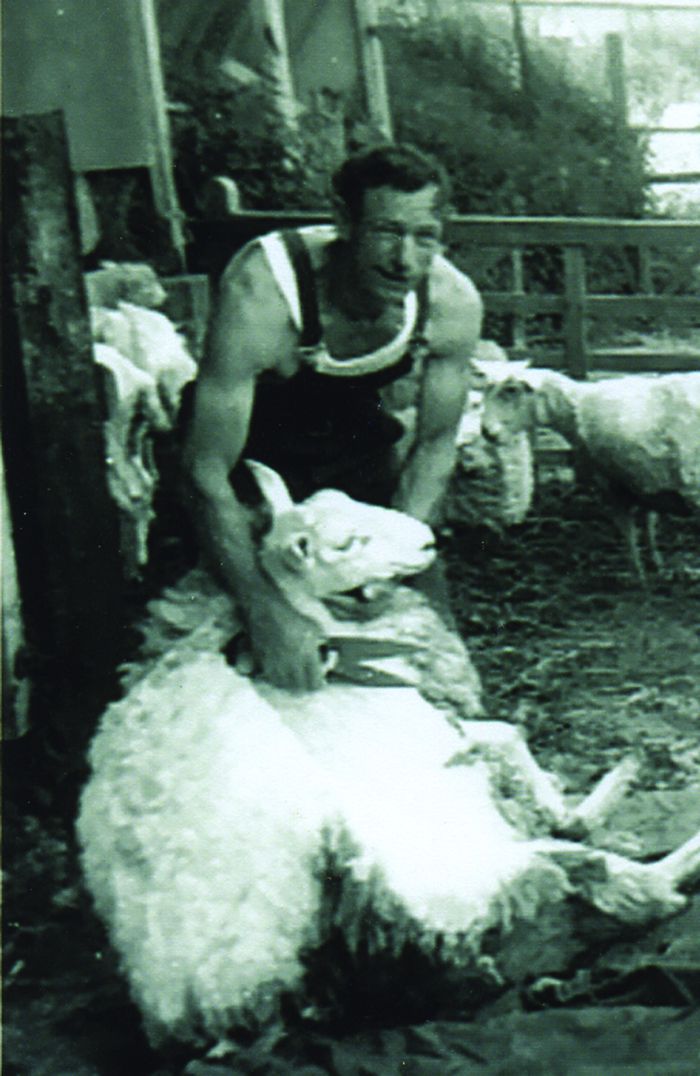

From Haremere he went to Boarzell, Ticehurst, as a shepherd. Always insisting on shearing his flock by hand – “It’s better for the sheep” – he used a pair of old-fashioned sheep shears he found in a hedge and was proud of the record number of sheep he could shear in an hour.

A highly intelligent, wise, deep-thinking man, attuned to the soil, Peter was well aware that organic methods are the only viable way of farming. He hated being obliged by later employers to use pesticides and artificial fertilizers. He said, “The land is our life and food. Without the land there is no life.”

He did not want to retire, and was fighting through the Farmworkers’ Union to stay in his tied cottage when tragedy struck. His daughter Jane died in his arms at the age of nineteen. Peter was devastated. Heartbroken, he returned to his early roots in Bohemia. He carried on doing farming and building work, caring for his wife, who became an invalid, and two cousins whose health was broken in the Robertsbridge gypsum mines. After his wife died two years ago, Peter, a gentle, loving, sensitive man, keenly felt the lack of someone to care for. It left a gap in his life from which he never really recovered.

It was fitting that he died the day before harvest began at Barnhorn, where he had worked for so long. He was buried in his farmworker’s clothing, with soil and ears of barley from Barnhorn as grave goods. Instead of flowers he had a sheaf of wheat intertwined with cornflowers and sunflowers. His daughter Anne said, “I would have liked his scythe to have been borne along on top of his coffin, but it would probably be against Health and Safety.” Asked if his coffin was to be drawn by horses, she said, “No, they wouldn’t be the faces of horses he had known. He would have wanted carthorses.”

o Several extra photos of Peter may be viewed at www.bohemiavillage.com (issue 71).

Leave a Response

You must be logged in to post a comment.